A booklet printed in 1933, published by Lunenburg Exhibitors Ltd., as a fundraiser to send Bluenose to Chicago for the World Fair.

It is important to note this book was published nine years before ‘Bluenose’ sank in 1946, and before she sailed to England to represent Canada at King George V Silver Jubilee in 1935, before her masts were removed in 1936, before the dime was minted bearing the Bluenose image in 1937, before she beat the Gertrude Thebaud in her final international racing series in 1938, and before she was sold to the West Indies Trading Company in 1942…

However, it is an important record of the Bluenose history, written as she was perceived in her heyday. The images included are those that were in the book.

In view of the worldwide interest in her career, invitations were extended to the “Bluenose” to participate in the “Century of progress” Exposition at Chicago in 1933. Through a number of public-spirited Lunenburg citizens, this was made possible, a company being formed – Lunenburg Exhibitors Limited, under the presidency of W.H. Smith – to sponsor the visit of the “Bluenose” to Chicago as Canada’s official representative at the World’s Fair.

In view of the worldwide interest in her career, invitations were extended to the “Bluenose” to participate in the “Century of progress” Exposition at Chicago in 1933. Through a number of public-spirited Lunenburg citizens, this was made possible, a company being formed – Lunenburg Exhibitors Limited, under the presidency of W.H. Smith – to sponsor the visit of the “Bluenose” to Chicago as Canada’s official representative at the World’s Fair.

Truly it is an ill wind that blows nobody any good, and a stiff breeze off Sandy Hook one summer’s day in 1920 – though it interrupted the contest between two crack racing yachts for the America’s Cup – was to help materially to bring worldwide fame to a schooner yet to be built.

It happened in this way. That great old sportsman, Sir Thomas Lipton, was making another of his gallant but unsuccessful attempts to lift the America’s Cup, and on one of the days appointed for the series of races, when a stiff breeze was whipping u the whitecaps, the judges decided to postpone the race for better weather.

And so, to the disappointment of the spectators gathered to watch the day’s race, the “Shamrock IV” and the “Resolute” remained at their moorings. The incident led to much comment and discussion. Some defended the action of the judges; others claimed the postponement unnecessary; whilst the attitude of deep sea fishermen, who were following the races with interest, was frankly scornful. “Call that a breeze? They ought to see what we can do,” said they.

An opportunity was soon to come, for within a few weeks, arrangements had been made for the holding of an annual international race for deep sea fishing schooners. The result of the first of these contests held off Halifax in October, 1920, was a decisive win for the American representative, the “Esperanto,” of Gloucester, which took two straight races from the “Delawana,” of Lunenburg, representing the Nova Scotian fleet.

This was a sad blow for Nova Scotians, and especially for Lunenburg, but no later than march in the following Spring a new challenger, bearing the proud name of “Bluenose,” designed and built to bring the coveted Trophy to Nova Scotia, was launched at Lunenburg. And this she did. For after a season of deep sea fishing, the “Bluenose” entered and won the eliminating races for Nova Scotian vessels, and a week or two later met and defeated “Elsie,” of Gloucester, for the International Fishermen’s Trophy.

And today, after twelve strenuous seasons on the Banks, the gallant “Bluenose” is as fast and fine a vessel as ever, famed in sailing circles the world over. Queen of the North Atlantic fishing fleets, and yet to be defeated in an International Trophy event.

The Building of the Bluenose

Anyone visiting the fishing port of Lunenburg, Nova Scotia, in the early Spring of 1921 must have noticed an air of suppressed excitement which seemed to pervade the whole town and district. And, one might add, as throwing a sidelight on the situation, Lunenburg does not easily become excited. The little town still exhibits many of the characteristics of the Hanoverians who founded it one hundred and eight years ago.

Something exceptional was obviously in the offing, and discreet enquiry would have centred the excitement around a new schooner, rapidly nearing completion in the shipyards of Smith & Rhuland. But what, you may ask, could one more fishing vessel possibly mean in the life of Lunenburg, home port of the largest deep sea fishing fleet in America? Merely as a fishing schooner it could mean little – the yards of Smith & Rhuland alone had launched 120 of them – but as challenger for the International Fishermen’s Trophy, built to avenge the recent defeat of the “Delawana,” it was a horse of a different colour and carried the high hopes of every Lunenburger.

Something exceptional was obviously in the offing, and discreet enquiry would have centred the excitement around a new schooner, rapidly nearing completion in the shipyards of Smith & Rhuland. But what, you may ask, could one more fishing vessel possibly mean in the life of Lunenburg, home port of the largest deep sea fishing fleet in America? Merely as a fishing schooner it could mean little – the yards of Smith & Rhuland alone had launched 120 of them – but as challenger for the International Fishermen’s Trophy, built to avenge the recent defeat of the “Delawana,” it was a horse of a different colour and carried the high hopes of every Lunenburger.

From the day the challenger was first planned – and, mind you, the new schooner was a co-operative affair, planned and paid for by a syndicate not of millionaires but of Nova Scotians of moderate means – enthusiasm had never wavered, and all Canada was watching her construction with friendly interest and encouragement. Her keel had been laid with unusual ceremony, the Duke of Devonshire, then Governor-General of Canada, making a special visit in order to drive the first spike. And now the “Bluenose,” as she was to be named, was almost ready for her first tests. How would she fare? Seaworthy she was sure to be but would she be fast, fast enough to beat the Gloucestermen?

Lunenburg and Gloucester schooners, be it explained, represent two distinct types. The one – in the absence of large markets for fresh fish on the eastern seaboard in Canada – has to be built to stand long weeks on the Banks, accumulating a heavy cargo of cod, and then carry it, salted, to Portugal, perhaps, or the West Indies, or Brazil. In other words the Lunenburg schooner is a freighter as well as a fisherman. The duty of a Gloucester boat, on the other hand, is to carry smaller cargoes of freshly caught fish as quickly as possible to nearby markets, Boston, Gloucester, or New York.

In these circumstances, speed naturally takes precedence over carrying capacity in the American fishing schooner – whilst in the Nova Scotian vessel carrying capacity is even more important than speed. The problem then, which faced Lunenburg during the winter of 1920-21 was that of getting greater speed from the Lunenburg type of schooner without any sacrifice of freighting qualities.

Whether this was possible or no did not remain undecided for very long, for on March 26th, 1921, the new schooner was launched and a few weeks later, on April 15th, was ready to make her trial spin. Enthusiasm by now was frankly at a fever heat, and crowds lined the wharves and waterfront, and the windows and tops of buildings, to watch her make it. Everything went satisfactorily. Paced by two other schooners, and in the able hands of Captain Angus Walters – already famous amongst the fishing fleets for his skill and judgment and courage, and soon to acquire even wider renown – the “Bluenose” quickly proved her handling qualities, showed marked ability in working to windward, and gave promise of the speed that was in her.

Whether this was possible or no did not remain undecided for very long, for on March 26th, 1921, the new schooner was launched and a few weeks later, on April 15th, was ready to make her trial spin. Enthusiasm by now was frankly at a fever heat, and crowds lined the wharves and waterfront, and the windows and tops of buildings, to watch her make it. Everything went satisfactorily. Paced by two other schooners, and in the able hands of Captain Angus Walters – already famous amongst the fishing fleets for his skill and judgment and courage, and soon to acquire even wider renown – the “Bluenose” quickly proved her handling qualities, showed marked ability in working to windward, and gave promise of the speed that was in her.

Lunenburg returned happily to work, confident that the new schooner was destined to bring the Trophy to Nova Scotia and so wipe out memories of the previous defeat. And the “Bluenose,” after a brief call at Halifax, where she received the kind of reception usually accorded to visiting royalty, set forth on her first trip to the banks as a deep sea fisherman. For the conditions governing the Trophy Contest, in order to prevent the building of “freaks,” insist that the two vessels chosen to represent the American and Canadian fishing fleets must be bona fide deep sea fishermen and have spent at least one season on the fishing grounds.

On the Banks

The “Banks,” as they are called in maritime circles, are large areas of shallow water in the North Atlantic, shallow enough in many places for vessels to ride at anchor. Actually, these submerged sandbanks form part of a plateau which follows the coastline closely from Florida to Maine and then swings out into the Atlantic in a north-easterly direction. Largest if them – there are fourteen important Banks in the group – is the Grand Bank, some 36,000 square miles in extent and lying south-east of Newfoundland, but in all, they cover double that area and form the most extensive cod fisheries in the world. During the past thirty years, for example, they have yielded an average annual supply of more than eleven hundred million pounds of cod.

The “Banks,” as they are called in maritime circles, are large areas of shallow water in the North Atlantic, shallow enough in many places for vessels to ride at anchor. Actually, these submerged sandbanks form part of a plateau which follows the coastline closely from Florida to Maine and then swings out into the Atlantic in a north-easterly direction. Largest if them – there are fourteen important Banks in the group – is the Grand Bank, some 36,000 square miles in extent and lying south-east of Newfoundland, but in all, they cover double that area and form the most extensive cod fisheries in the world. During the past thirty years, for example, they have yielded an average annual supply of more than eleven hundred million pounds of cod.

When one comes to think of it, the humble codfish has played no mean part in the discovery and development of Americas. Gold may have served to draw the Spaniards to Central and South America, but long before that the cod had drawn hardy European fishermen to North America. “Follow the fish” has ever been the rule of the deep sea fisherman, and when the American Continent was first “officially” discovered (the West Indies by Cabot, in 1497), Europe had already long been drawing supplies of cod from the teeming Banks.

The earliest fishermen to visit the cod banks of the North Atlantic, and make a practice of it, were apparently the French – Normans, Bretons, and Basques. Cape Breton, one of the oldest place names in America, is a relic of these early visitors. But the Spaniards and Portugese were not far behind the French. – there is definite historical evidence that all three were frequenters of the Grand Bank before the year 1502 – and a little later the English had no less than 200 sail and 8,000 men working off Newfoundland. These fisheries were later to prove an invaluable source of manpower to the English when they came to wrest the mastery of the sea in turn from Spain and Holland. For they provided a plentiful supply of seamen trained in the hardy school of the North Atlantic.

The “Bluenose” as a Fisherman

Now, as then, a fishing trip to the Banks is no mere pleasure jaunt, either for boat or men and the “Bluenose,” both on her first and her many succeeding trips, followed the life of a typical Lunenburg fishing schooner. She is usually away on the grounds, for example, from six to eight weeks at a spell, through fair weather and foul. And her men are kept hard at work daily from before dawn until after dark, for there’s no eight-hour day on the Banks!

Now, as then, a fishing trip to the Banks is no mere pleasure jaunt, either for boat or men and the “Bluenose,” both on her first and her many succeeding trips, followed the life of a typical Lunenburg fishing schooner. She is usually away on the grounds, for example, from six to eight weeks at a spell, through fair weather and foul. And her men are kept hard at work daily from before dawn until after dark, for there’s no eight-hour day on the Banks!

This steady grind continues through the entire fishing season – from March or the beginning of April until the latter part of October – in which time three or four complete trips to the Banks can usually be made. But every man works with a will, for every man has a pre-arranged share in the schooner’s earnings. If the vessel makes money, so do the men. It’s a partnership proposition.

The fishing crew of the “Bluenose” consists of twenty-one men – sixteen “dorymen,” a “dressing crew” of four, and last but not least, a cook – and the actual fishing is carried on in this way. With the schooner riding at anchor a number of trawl lines, each about a mile and a half in length, are set out. The ends of the lines are attached to kegs or buoys, which serve both to support the lines and act as “markers.” And four times a day, storms permitting, the lines are visited, the caught fish removed and hooks re-baited, by dorymen rowing out for this purpose, two men to a dory.

In the morning, for example, after preparing the necessary bait, the men set out for the first “under-run,” as it is called. The lines are located, though sometimes with difficulty, by means of the kegs which keep them afloat, and the heavy work then commences of overhauling the lines. For this, the two dorymen sit facing one another, with tubs for fish and bait placed between them, and the “bowman” drags the line over the dory towards the “afterman.” He in turn removes the fish, re-baits the hooks wherever necessary, and passes them over the dory’s side back into the ocean.

This “under-run” method of fishing – so called because the dory is run under the raised trawl line – is the customary practice with Lunenburg fishermen and each under-run takes from two and a half to three hours, even under favourable conditions, to complete. (If the catch proves unusually heavy, or the line gets snarled, or breaks, or if fog comes up, the time may naturally be very much longer). As each dory returns to the schooner with its catch, the fish are turned over to the “dressing crew” – who, together with the cook, always remain on board – and the cod, after being carefully headed, split, cleaned, and washed, are placed in piles in the hold of the schooner and salted.

When the dories return from the first under-run, usually about 6 o’clock in the morning, the cook has breakfast waiting – and the men, as may be imagined, are ready for it. With several hours of strenuous work in keen, salty air as an appetizer, meals on a “banker” are something more than mere snacks, and the cook’s job in consequences is no sinecure. After breakfast the men set off for the second under-run, returning about 10:30 a.m., all being well, for dinner. The end of the third run, about 4:30 in the afternoon, brings them back to an early supper, and the final under-run for the day is finished shortly before dark.

The day’s work is not finished, though, until all fish have been salted down, and when the catch has been a good one the dorymen have usually to set to and give the dressing crew a hand. But eventually the last codfish is tucked away under salt, and the day’s work is done. Then, once a final supper has been stowed away, there is a general movement for’ard, where the bunks are situated. The only exceptions are the unfortunates who have to take their turn on the night watch.

It’s no job for weaklings or shirkers, this work on the Banks. For the work is hard, the hours long and exhausting, and danger is always at hand. There’s the danger of being run down at night or in fog by liners…of being dashed from the wave-swept deck in stormy weather… of shipwreck…and foundering. And for the dorymen there’s the added risk of getting lost in the dense fog so prevalent on the Banks in summer…or of the dories being swamped. But Lunenburgers are loyal to the life they know and love – and, with all its hardships and risks, it breeds a great race of men.

The Racing “Bluenose”

At the end of her first season on the Banks, a highly successful one, too, the “Bluenose” returned to port and was groomed and prepared for the Nova Scotia Fleet race – the winner of which would automatically become both Nova Scotia champion and challenger for the International Fishermen’s Trophy. The race was held off Halifax, October 15th and 17th, and on both days the “Bluenose” defeated the other seven entrants, and so qualified to meet the American defender.

As the holder of the International Trophy, the “Esperanto,” of Gloucester, had unfortunately been lost at sea, another schooner had to be chosen to represent the American fishing fleet in the 1921 contest. This proved to be the “Elsie,” also of Gloucester, and the races were again held off Halifax, October 22nd and 24th. On both occasions, the “Bluenose” led the “Elsie” over the finish line, the first day by thirteen minutes, the second day by eleven. Lunenburg, through the “Bluenose,” had achieved her ambition. The International Trophy, donate the previous year by a Nova Scotian, W.H. Dennis, of the Halifax Herald, had come to Nova Scotia.

The following year, 1922, the “Bluenose” repeated her successes, first winning the Nova Scotia Fleet Race at Halifax and then going to Gloucester to defend the Trophy against the fishing schooner “Henry Ford.” After the first race had been declared “no contest” and the “Henry Ford” had won the second in a light breeze, by 2 minutes, the “Bluenose” was favored with heavier weather – in which she revels – and proceeded to win the next two races, together with the championship.

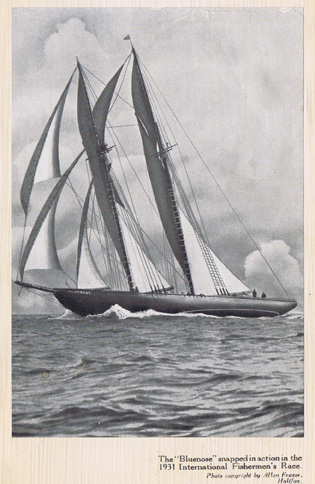

In 1923 the “Bluenose” met another Gloucester challenger, the “Columbia,” and finished ahead in the first two races. As a result of a protest, however, the second race was later awarded to the “Columbia” on a technicality, and the “Bluenose” was withdrawn from the contest, retaining the championship. For some years the races were then abandoned,a nd not until 1931 was another race held for the International Trophy.

But in October 1931, though now a veteran of many hard seasons on the Banks, survivor of various mishaps – once almost being wrecked when she spent four days on the rocks in Placentia Bay, Newfoundland, in 1929 – the ten year old “Bluenose” met the year old “Gertrude L. Thebaud,” of Gloucester, for the supremacy of the North Atlantic. In the first race the “Bluenose” led her rival by 36 minutes but as both vessels exceeded the time limit of six hours the race was declared “no contest.” Two days later, however, the “Bluenose” defeated the “Thebaud” again by a wide margin, and then put the issue beyond doubt the following day.

Today, after twelve years of hard service, the “Bluenose” remains the champion of the North Atlantic fishing fleets, holding the record for the largest single catch of fish ever brought into Lunenburg and yet to be defeated in an International Trophy Contest. She has won international reputations for her designer, W.J. Roué, of Halifax, and for the man who has “skippered” her so successfully throughout her eventful career – Captain Angus Walters. And for herself, she has won an extraordinary respect and affection in the hearts of a multitude of people. No fishing schooner has ever matched her record. Long life to her!